Date Posted: 2020-07-11

by Charles Suhor (from Aug. 2018 Issue Jazzology Newsletter)

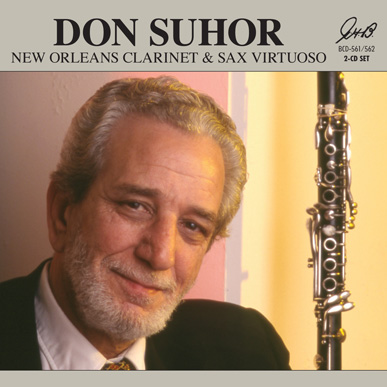

A jazz fan in New Orleans from the post-WWII years to the end of the century might or might not have heard one of the most gifted players of the time — Don Suhor (1932-2003) played constantly and was admired by musicians in all jazz styles, but he had no concern for recognition, let alone fame. His first priority was to find musical settings, traditional or modern, that made room for his love of improvisation. The GHB 2-CD set (BCD-561/562), Don Suhor—New Orleans Clarinet and Alto Sax Virtuoso, provides a legacy of his unheralded talent.

In his teen years he mastered the Dixieland and swing era combo repertoires and dozens of popular standards on clarinet. He went on to integrate Dixieland and modern jazz in a "bopsieland" synthesis, at the same time creating a highly original brand of bebop on alto sax with an underground cadre of pioneering modernists in the French Quarter. I was the awed kid brother, following Don as he entered many doors of music, taking from each whatever he found interesting and enriching. Don's line of development was unlikely, but he came about it honestly. The third in a family of five children from the Ninth Ward, he took up clarinet at age 12 when our mother Marie, a first- generation American, insisted that he get "some kind of musical education." Don chose clarinet because he had heard Artie Shaw on swing era records that our older siblings, Mary Lou and Ben, had bought —and because he thought Shaw looked handsome playing the instrument.

In his teen years he mastered the Dixieland and swing era combo repertoires and dozens of popular standards on clarinet. He went on to integrate Dixieland and modern jazz in a "bopsieland" synthesis, at the same time creating a highly original brand of bebop on alto sax with an underground cadre of pioneering modernists in the French Quarter. I was the awed kid brother, following Don as he entered many doors of music, taking from each whatever he found interesting and enriching. Don's line of development was unlikely, but he came about it honestly. The third in a family of five children from the Ninth Ward, he took up clarinet at age 12 when our mother Marie, a first- generation American, insisted that he get "some kind of musical education." Don chose clarinet because he had heard Artie Shaw on swing era records that our older siblings, Mary Lou and Ben, had bought —and because he thought Shaw looked handsome playing the instrument.

Don took beginners' group classes at Werlein's Music Store under Johnny Wiggs, the noted Bixian cornetist who became a co-founder of the New Orleans Jazz Club. His immediate enthusiasm led to serious study with Emanuel Alessandra, oboist with the New Orleans Symphony. Challenged by the rigorous approach, he gamely did traditional solfeggio exercises, practiced long tones, and was a quick study at reading music. Pete Fountain, who also studied with Alessandra, and Don were among the entrants in Benny Goodman's search for the city's most promising young clarinetist in 1947 when Goodman came to town to play with the New Orleans Symphony. The

finalists were Don, age fourteen, and nineteen year-old Don Lasday, who later became a versatile reedman and teacher in the city. Lasday weaved capably though several blues choruses. Don, not yet a fluent improviser, won the competition by playing, ironically, two memorized Artie Shaw solos from the Gramercy Five recordings, both rendered with flawless control of feeling and inflections.

Formal training was only part of the story. This was the time of the popular postwar revival in New Orleans, and the music came in through the pores. Sharkey Bonano, George Lewis, Papa Celestin, Tony Almerico, Paul Barbarin and others brought to the forefront jazz that had been the province of aficionados like Bill Russell and Al Rose.

Don and his school friends started a combo to play for dances at the W.O.W. Hall. Band director Charlie Wagner, who had once played trumpet across the street from Bix Beiderbecke, enjoyed talking to jazz-oriented students about the music and its history. During marching band practice in football season, Don would occasionally jam contrapuntally during the trio sections of marches, with Wagner's tacit approval. While the dance band was on break at school events Wagner occasionally played piano with a breakout group of students who could fake and jam.

Don also gigged with solid young Irish Channel musicians like the Assunto brothers and trumpeter Al McCrossen. He worked weekends with veteran trumpeter Red Hott, an Armstrong devotee, who was especially fond of "Lil' Donnie" and brought him to jam at New Orleans Jazz Club meetings. At age 16 he sat in with Sharkey's Kings of Dixieland at a concert at the Municipal Auditorium. Don persuaded me to accompany his front-room solo jams. At first I used coat-hanger sticks, cardboard boxes, a pot cover cymbal, and a small stepstool for a woodblock. I bought a cheap second-hand drum set from Phil Zito. Inspired by Goodman, he tested himself—and me—with breakneck tempos on tunes like "The World is Waiting for the Sunrise."

Don took up alto sax in his late high school years and was soon playing in local dance bands. He chose alto sax because he liked the bright sound of the instrument in big band sax sections. But he became enamored of a radically different sound when he heard the dauntingly complex early recordings of Lee Konitz and the Lenny Tristano school. Jamming in our living room, I could almost see the wheels of his mind turning as he wove out long, complex solo lines. On clarinet, he raised the bar by playing tunes like "I've Got Rhythm" in the standard key then moving up a half step to improvise in every key.

Don enrolled in the Loyola Music School in 1950. As a freshman he played third alto in the big band amid veteran musicians — veterans, literally. Many were Swing Era ex-servicemen studying under the GI Bill of Rights. Younger Loyolans, like Al Belletto, and bassist Oliver "Stick" Felix, gravitated toward the French Quarter, where modernists eked out a living at strip joints. During after-hours sessions, Don's conception on alto shifted from Konitz's ethereal style to straight be-bop. The superb alto saxophonist Joseph "Mouse" Bonati, who'd recently arrived from Buffalo, became his idol, along with, inevitably, Charlie Parker. Don became a hard- swinging bopper among the pioneering artists who were nowhere on the radar of the press or the general public.

Over the years Don's style grew increasingly distinctive. On clarinet, his tone and vibrato took on a rich, impassioned quality that stamped him as a New Orleans musician. His easeful merging of prodigious technical skills and knowledge of chords into a "bopsieland" synthesis stimulated his fellow musicians. On both alto sax and clarinet, he incorporated notes above the normal range of the instruments into his solos lines. This was never employed as a gimmick; the notes were simply there, like all others, accessible for use in melodic improvisation.

Except for a two-year Army stint in 1954 and a brief subsequent stay in Washington D.C., where he jammed with Shirley Horn, Buck Hill, and others, Don never left New Orleans. He had lucrative offers to go on the road but preferred to stay among family and friends in the beloved city where he could improvise, improvise, improvise. In college his reading skills had put him in demand for sax section work in local dance bands. After subbing with the excellent Lloyd Alexander big band, he remarked, "Yeah, Charlie, it's really a good band, but you know, I didn't get much chance to play." By which he meant, to improvise beyond the usual solo space given to the third alto chair. At the 1980 Jazzfest he sight-read Lionel Hampton's book, a relatively easy assignment. But Kent Larsen, longtime Stan Kenton trombonist who played with Don during their Army years, assured me that Don had the reading and jazz chops to hold a chair in Kenton's celebrated sax section.

Improvise he did, for fifty-five years at innumerable New Orleans jazz venues, among them, Al Hirt's, the Blue Room, Commander's Palace, Court of Two Sisters, Crazy Shirley's, Famous Door, Jazzfest, Maison Bourbon, Palm Court Jazz Café, Playboy, Prima's 500 Club, Sho'Bar, Snug Harbor, Steamer President. His sustained work at luncheon sites enabled him to double up at nights, sometimes playing more gigs than days in the year.

In 2002 Don Suhor was stricken with lung cancer. A benefit jam session was held in January of 2003 at the Palm Court Café, and though Don was too ill to be there, over 250 musicians and friends attended. He died a week later at the age of 70.