Date Posted: 2013-10-29

by Jon Pult

A measure of the popularity Cliff “Ukulele Ike” Edwards enjoyed in the 1920s can be found at the beginning of Metro Goldwyn Mayer’s Hollywood Revue of 1929, that initial movie musical featuring a “Galaxy of Stars,” among them Joan Crawford, Laurel and Hardy, Marion Davies and Buster Keaton. Edwards was also in that number, another constellation in the burgeoning Hollywood firmament. He first appears onstage while the mostly forgotten leading man, Conrad Nagel, and the wholly forgotten singer Charles King, are making their way through a bit of business regarding introductions. King asks a large cast of dancers seated on stage, “Who is the greatest interlocutor in the world?” The assembled chorines reply in unison “Conrad Nagel!” while Nagel feigns humility. Then King asks, “and who is the greatest lover on the screen?” In response, Edwards, small and effete, enters from stage right with an exaggerated sway and replies, “None other than Little Cliffy.” He assumes an odd, leaning pose, cradling his ukulele and batting his eyes like a starlet.

“Well, hello,” Nagel says, “who are you?”

“Oh, don’t tell me you haven’t heard of Little Cliffy?” Edwards says.

“Well, Cliffy who?” Nagel says, flummoxed.

“You evidently buy lots of phonograph records?” Cliffy asks.

“Yes,” Nagel says.

“All right, listen.” Edwards begins strumming his uke and goes into a kind of scat singing he called “effin,” an odd sounding rhythmic vocalization he first showcased on the 1922 recording “Virginia Blues” with Ladd’s Black Aces, for which he became famous. Nagel smiles and nods in recognition, he looks skyward, his body language saying, “Oh, of course, Little Cliffy.” Nagel puts his arm around Edwards who continues to strum and offer his high-pitched moans.

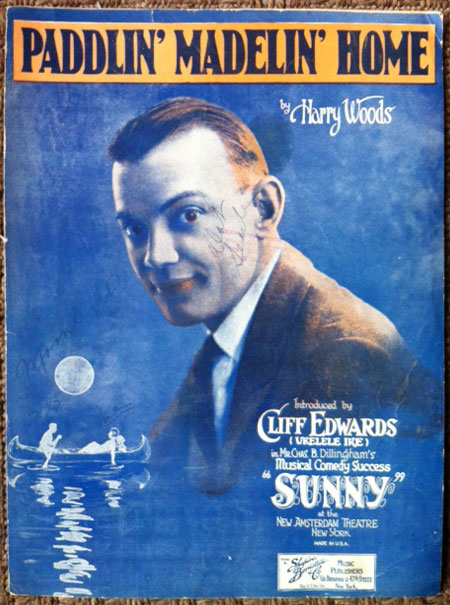

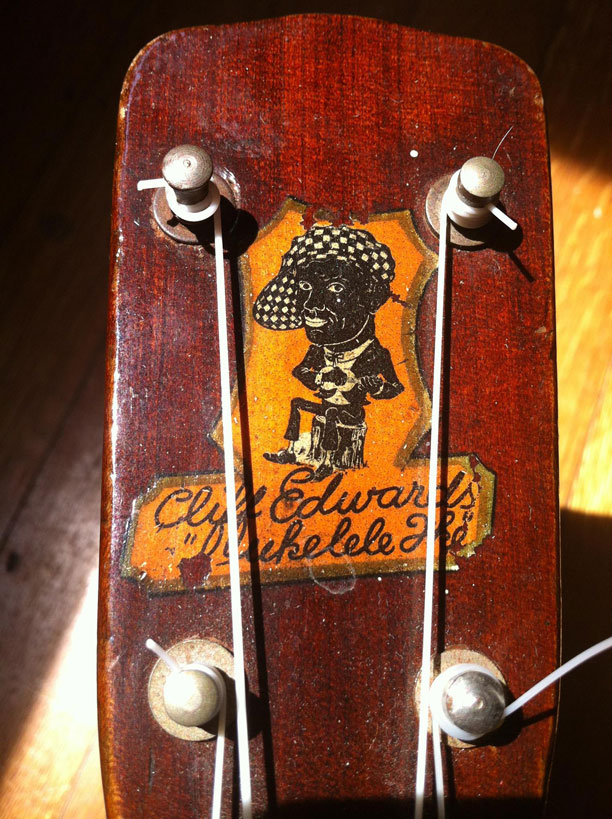

Nagel’s reaction was understandable. While the twenties roared, the voice of Cliff Edwards sold untold millions of records. He almost single-handedly popularized the ukulele, making it de rigueur accoutrement with the raccoon coat set, another symbol of the reckless Jazz Age. He thrilled Vaudeville audiences, and starred on Broadway. “Ike stole the show,” Fred Astaire said regarding Edwards’ introduction of Gershwin’s “Fascinatin’ Rhythm” in Lady Be Good in 1924. In the mid-twenties anyone could go to a record shop and buy a statuette of “Ukulele Ike,” in black face strumming a uke while seated on a tree stump. The local music shop carried the P’Mico “Cliff ‘Ukulele Ike’ Edwards” model ukulele. One could buy it and learn to play “That’s That” from Ukulele Ike’s Comic Song Book Volume Two, the introduction to which calls Edwards “The master of America’s own beloved instrument, the unassuming ukulele.” His face, too, was familiar, staring from the covers of sheet music hits like “Paddlin’ Madelin’ Home,” and “Who Takes Care of the Caretaker’s Daughter While the Caretaker’s Busy Taking Care?” Later in Hollywood Revue he would introduced a little tune that would become a standard (and, later, his theme), “Singing in the Rain.”

Today, try to talk to someone about Cliff Edwards and initially you’ll receive a Nagelian “Who?” But instead of launching into a wild, scatted chorus of “Hard Hearted Hannah,” instead say “Jiminy Cricket” and that nod of recognition is instantly forthcoming. While that role alone should have secured him a perch in the lower reaches of our cultural space (his rendering of “When You Wish Upon a Star” won an Academy Award and became Disney’s theme), it is an anonymous sort of fame; most people merely remember the voice of a cartoon insect.

Edwards’s accomplishments in the twenties put him on a tier just below Eddie Cantor and Al Jolson, but unlike their work, which can seem far away and slightly tinny to the contemporary ear, Edwards’s best records of the twenties still contain a sense of immediacy, a timelessness and resilience that few recordings of the period can muster. Listen to his 1925 recording of “Dinah” with cornetist Red Nichols, for example; it is completely alive. Or his 1928 recording of “Stack-o-Lee” with Joe Venuti and Eddie Lang, where his singing is bluesy and modern. Although writers have devoted many words to the lives and work of “Banjo Eyes” and “Jolie,” an account of Cliff Edwards’s career appears in a single discography, with short biographical sketch, cheaply typeset on a dot-matrix printer and costing $80.95, the province of collectors. Yet to view Edwards’s career in thumbnail is to read of the rapid rise and terrible fall of one of the twenties biggest stars.

Clifton A. Edwards was born on June 14, 1895 in Hannibal, Missouri. He made hundreds of recordings over the course of his career , all told more than 450 distinct titles. He appeared or was heard in eighty-seven motion pictures and featured regularly in Vaudeville, on Broadway, and on the radio. Edwards even had an early TV show. But his private life, like that of many a celebrity, got the best of him in the end. Edwards made and lost, millions of dollars. Despite his success as Jiminy Cricket in 1939, by the late 1950s he was a recovering alcoholic combing the back lots of the Disney studios looking for fill-in jobs. “Ukulele Ike,” died in 1971 of a heart attack while living in a convalescent facility in Los Angeles, his body lay unclaimed for days.

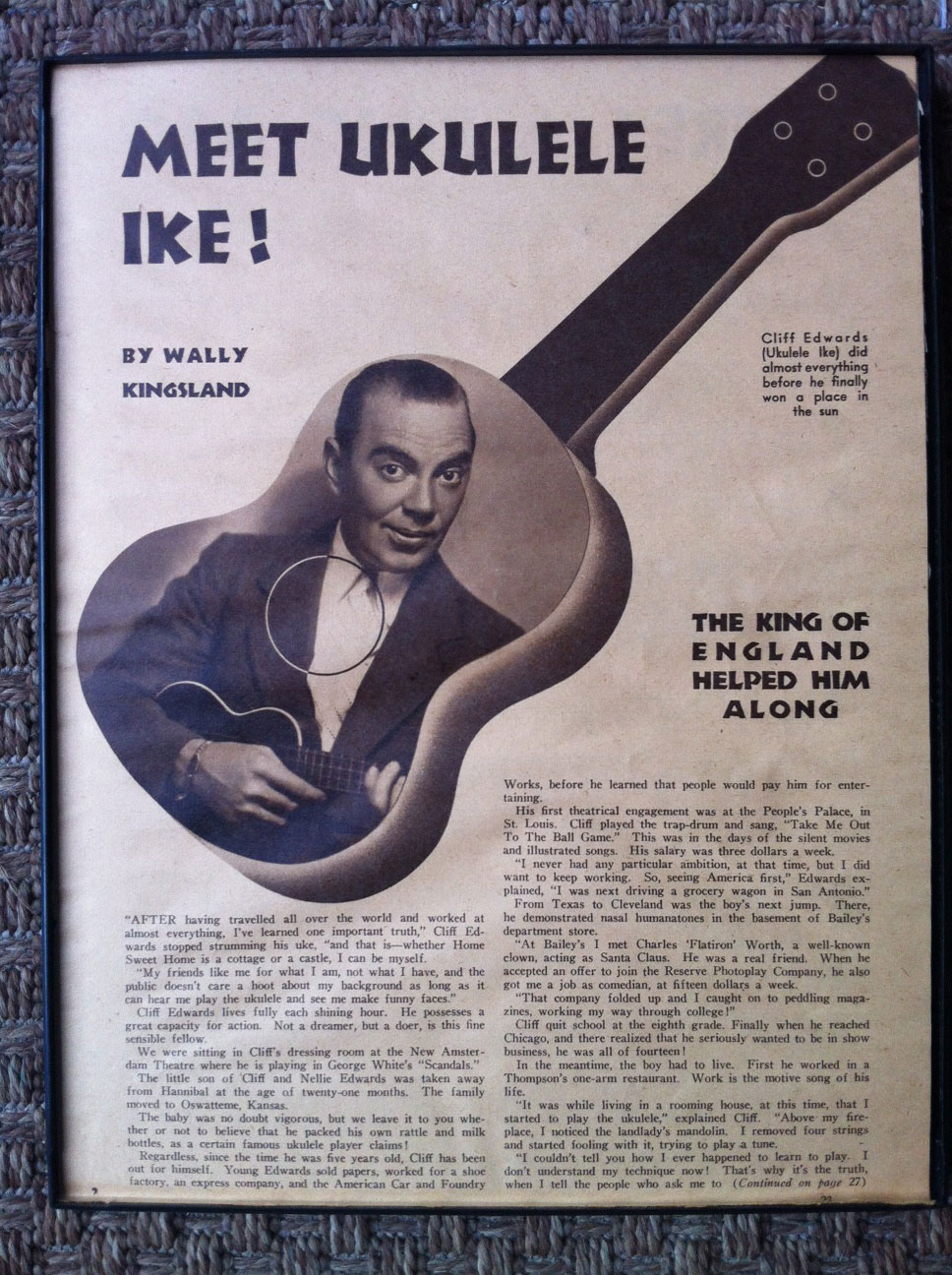

Ironically, researching the life of Cliff Edwards, despite the hours of recorded material and film footage—despite being able to see him sing and joke just as his original audiences did—is a bit like researching the life of someone who never left the stage, a figure who remains in the recorded world of sound and image, and in the sensational pages of tabloid headlines. Would that he might step down into the audience and flesh himself out, like the handsome leading man in Woody Allen’s Purple Rose of Cairo. Instead, all we have been left with, for the most part, is his image—the public persona he created, the Vaudeville clown or the role of Hollywood star that studio press agents delineated in publicity tracts: “Cliff Edwards lives fully every shining hour...Not a dreamer, but a doer, is this fine sensible fellow.” Then there are advertisements for his records, teasers that suggest his popularity, like a quarter pager in the Charleston, West Virginia Daily Mail from November 1924 that reads, simply: “Ukulele Ike – Hear these records….That’s all we ask.”

Indeed, the truest expressions of Cliff Edwards the entertainer come from the recordings themselves. Listening for clues in the grooves of the old shellac discs, attempting to ferret out something of his personality in the way he phrases a lyric is to find a certain comic sense in his reading of “It Goes Like This That Funny Melody,” improvising a bit about President Coolidge with the line “and Coolidge said,” followed by five seconds of silence, or a baseness in his original compositions “I’m Gonna Give it to Mary with Love,” or “I’m a Bear in a Ladies Boudoir.” Except for a few memorable roles, such as a reporter in His Girl Friday, Edwards spent his film career behind a slapstick mask as the effeminate ukulele-toting clown.

Sadly, perhaps the most complete record of his private life appeared in Hearst newspapers. There one can find inch upon yellow-column inch of reporting on Edwards’ personal woes: “Ukulele Ike Poor Provider, Wife Asserts” the headline screams. Below, Nancy Dover (the first Mrs. Edwards,born Lucille Kelley and also known professionally as Judith Barrett) is quoted telling the court “The constant [financial] worry affected my nervous system to such an extent that I required the care of a physician.” More such headlines, in the grand American tradition of tabloid style celebrity coverage, reek of the gossip surrounding his spiraling fame:

• Ukulele Ike tells of another man in divorce suit

• Ukulele Ike wins point in wife row

• Claim: Ukulele Ike’s wife in man’s pajamas at party

• Kiss throwing related by Ukulele Ike

• Ukulele Ike’s wife tells of Mexican Party

• Ukulele Ike’s wife tells of drinks

Edwards “won” the case on grounds of cruelty, but lost the financial battle. He was ordered to surrender half of his earnings for the rest of his life as alimony. Just two months later his only son lost his legs in a train accident prompting his first wife to ask for more money for prosthetics. He re-married in August of 1932 only to be divorced by October. A few years later he was sued by his accountant, his gardener and, as yet another headline explained, for non-payment of a “Hair Growing Bill.” The New York Daily News carried the headline, “Debts: $25,859 Assets: 2 Ukuleles.”

In a futile attempt to combat his tabloid reputation, Edwards, in a 1936 interview in Popular Song Magazine, said “The public doesn’t care about my background as long as it can hear me play the ukulele and make funny faces.” Within that reckless personal life, Edwards remains obscure, residing—as he himself admitted—in the realm of caricature.

The ranks of men and women who knew and worked with Cliff Edwards, those who would be able to give a sense of the man behind “Ukulele Ike,” are quickly dwindling. But I searched them out, hoping to put some flesh on the skeleton. A call to Buddy Ebsen (The Beverly Hillbillies’ Jed Clampett) who Edwards had starred with in Girl of the Golden West in 1938 yielded nothing more than “he was a fine ukulele player” between deep and raspy moans. Ebsen died two weeks later. Similarly, Disney animator Ward Kimball who was responsible for drawing Jiminy Cricket and had worked closely with Edwards for many years, told me simply “Cliff Edwards, it’s too late, it’s just too late.” Kimball’s obituary appeared in The New York Times within weeks of the conversation.

Other veterans of the Disney lot were able to pull back the curtain for me, if ever so slightly. George Probert, who worked in Disney’s music department, played clarinet on Edwards final jazz recording in 1958, “Ukulele Ike Sings Again.” He described Edwards as “a real loose character and a real professional.” He explained that another person at Disney, George Bruns, had wanted to do Cliff a favor and have him record. “We went into the studio and did the whole thing in three hours,” Probert told me. “Cliff knew who he was, and he knew exactly what he was doing.” Probert said that Edwards was friendly, but quiet. “He was pretty desperate for work in the late fifties and early sixties. He would just show up at the studio every day, sit down on a bench on the grounds and just hope for some voice-over work.” Occasionally his friends on the lot, wanting to help, would get him something on the Mickey Mouse Club. “By that time he was pretty far gone. He always had that quiet blank look of a reformed alcoholic. He had been at the top, but had just lost it.”

Most of the remembrances of Cliff Edwards come from the waning of his career and his time with Disney. Animator Frank Thomas (one of Disney’s “Nine Old Men,” he was responsible for some of the studio’s most iconic scenes), remembered auditioning Edwards for his role in Pinocchio, “We found him perfect for Jiminy Cricket” he told me, “His voice had gentleness and strength, it was defiant, he could get mad and be sympathetic. When he meets up with the Blue Fairy he is appropriately overwhelmed by her. My, he did a beautiful job on that voice.” Thomas sighed in the memory and continued. “The sad thing, though, is that it didn’t bring him a huge amount of publicity or money for that matter. He always hoped that we’d use him all the time, but at Disney everything had to be right and perfect for that particular picture. For Pinocchio he was perfect, but when it was through, well it was through.” Thomas said that Edwards was very important to the people at the studio. “I mean the song, ‘When You Wish Upon a Star,’ it identified the studio, it was our theme.”

Like Probert, Thomas recalled Edwards as always being around the Disney lot, hoping for work. “He got a few things, the lead Crow in Dumbo, for example, and he worked on the Mouse Club, wrote a few songs for the show.” As the years passed Thomas felt increasingly sorry for him. “I remember him telling a story one time about playing a show, a benefit, and singing ‘Fascinatin’ Rhythm.’ He sang us the whole song right there in the cafeteria: ‘Got a little rhythm, rhythm, rhythm, pitter pats through my brain.” Almost in a sort of reverie, Thomas was compelled to sing the whole song to me over the phone. “He was good guy, I guess, such a big shot in the early days, Ziegfeld Follies and all that, but alcohol got the better of him.”

In the mid-1950s the trombonist Don Ingle was playing in his father’s band, Red Ingle and the Natural Seven, when he met Edwards. From Christmas week 1953 through New Years day 1954 the group had an extended engagement at Louisville’s Iroquois Gardens. “It was a glorified roadhouse passing as a nightclub,” he told me, “an old resort-style place that featured supper shows and dancing.” That week Red Ingle got a call to go to New York to work on a television special and left his son Don as the leader of the band for the remainder of the engagement. For holiday week, the management put together a small variety show that the band accompanied. It included an eccentric dancer, a trio of singing girls, and the week's headliner Cliff “Ukulele Ike” Edwards. “I was 22 years old at the time,” Don Ingle said, “and, you know, to someone of my age Pinocchio was quite a big deal when it came out, Jiminy Cricket, heck, he was our man! So I admit it was a great thrill to be working with him.” Ingle soon found himself in the presence of a master vaudevillian. “I remember that he came into town and we had a single afternoon rehearsal, it probably didn’t even last an hour. It’s almost fifty years later and I still count it as the easiest rehearsal I ever made. He said, ‘Just do your thing, just noodle behind me, I’ll be alright.’ He was just a marvelous old entertainer,” Ingle explained, “his spiel was very simple, there was nothing elaborate just short and sweet little announcements between the songs, little Jazz Age references, like when we played ‘My Blue Heaven,’ he’d say ‘It cost me a lot of money to have someone steal this arrangement from Gene Austin.’”

Perhaps the anecdote that best captures Cliff Edwards and Ukulele Ike sharing the same stage, is the one Al Cormier told me. (I came across Cormier’s reminiscences from his childhood while looking for information about Edwards on the internet.) By Cormier’s recollection, it was in the mid-1940’s, perhaps 1945 or 1946, on 10th Street in Leominster, Massachusetts, when he was awakened late one evening by his father. It was so late, in fact, that it was early in the morning. “He woke me and my brother up and said that there was someone downstairs that he wanted us to meet. It was 2:30 in the morning and he had been at his Elk’s meeting and then out drinking with his friends.” As he tells the story he laughs, recalling that when he got downstairs all he could see was a small circle of light moving around in the corner. “When my dad turned the light on there was a man standing there, he was in his mid-fifties maybe, and I realized the light was coming from a bulb that was inside a ukulele. “Kids,” my father said “I’d like you to meet Ukulele Ike.”

It turns out that Edwards, plying the last vestiges of the Vaudeville circuit, had finished his show in town and didn’t have a place to stay so the senior Cormier brought him home. “My dad shut the light off and said, ‘Play for us.’ We kids sat there and listened to him sing ‘Toot, Toot, Tootsie Goodbye,’ and ‘I Cried for You.’ I had never heard anything like it.” At the time, Cormier didn’t realize that the man in his house was Jiminy Cricket. He found out at breakfast the next morning, while Edwards slept on the couch. As he walked to school he met up with a friend and excitedly said, “Ukulele Ike is at our house!”

“Who?” his friend said, like Conrad Nagel in Hollywood Revue, nonplussed.

“Jiminy Cricket, he’s asleep on our couch.” His friend smiled and nodded in recognition, his body language saying, “of course.”